Delaware lawmakers working to address food insecurity, childhood hunger

DOVER — One out of 10 Delawareans are living in poverty, and 1 out of 8 are hungry. Breaking the numbers down, 1 out of 5 children are struggling to find food.

That’s why …

You must be a member to read this story.

Join our family of readers for as little as $5 per month and support local, unbiased journalism.

Already a member? Log in to continue. Otherwise, follow the link below to join.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

Delaware lawmakers working to address food insecurity, childhood hunger

DOVER — One out of 10 Delawareans are living in poverty, and 1 out of 8 are hungry. Breaking the numbers down, 1 out of 5 children are struggling to find food.

That’s why Delaware’s General Assembly is working to eradicate hunger, with two initiatives that could have a profound effect on those experiencing a lack of access to reliable food sources — no matter their age.

While neither bill has become law with three weeks to go of the 2024 legislative session, the bipartisan attempts by Sen. Darius Brown, D-Wilmington, in the upper chamber, and Reps. Rae Moore, D-Middletown, and Bryan Shupe, R-Milford, in the House of Representatives, are making progress.

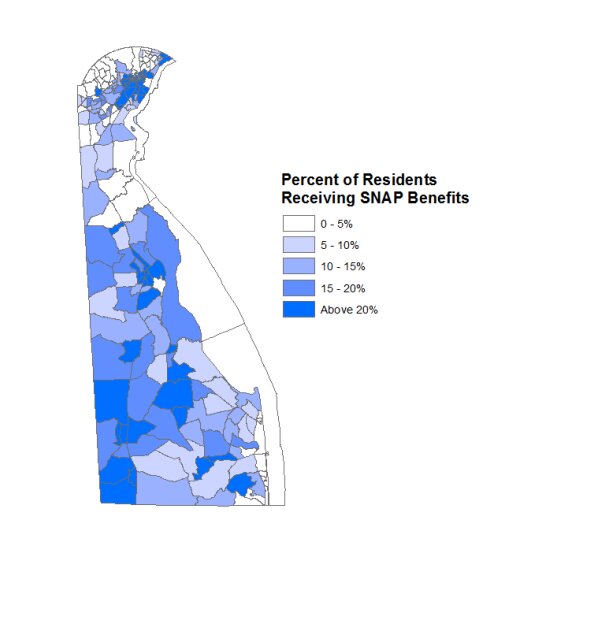

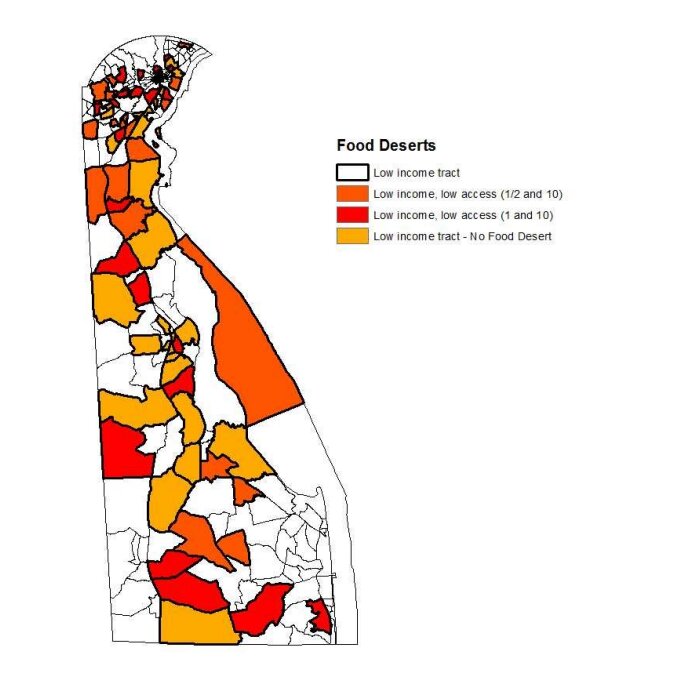

“There are 16 districts in the Delaware state Senate that have been identified with at least one census tract that qualifies as low-income or low-access. In the House of Representatives, at least 25 districts have at least one qualifying census tract identified as low-income or low-access,” Sen. Brown said, referencing the 62 total districts in the legislature.

In response to those numbers, he is seeking to create the Delaware Grocery Initiative, which would direct the Office of State Planning Coordination to study food deserts in urban and rural areas, and to send a report to the General Assembly and governor detailing the findings.

According to Senate Bill 254, “food deserts” are defined as areas with at least 20% of the population living in poverty or with median family incomes less than or equal to 80% of the statewide median household income, though that is dependent on whether the household’s location is contained in a statistical metropolitan area.

The deserts are also defined for rural and urban areas, locations where poverty statistics vary statewide.

In the First State’s rural areas, a food desert means that either a third of the population or 500 people live over 10 miles away from the nearest grocery store. In urban areas, it’s the same, but the distance is limited to a half-mile.

Sen. Brown’s bill would implore the planning sector to study the reasons for current market failures, potential policy solutions and geographic trends. It would also identify communities that are at risk of becoming food deserts, while introducing disparity studies for such populations.

Ultimately, it would provide financial assistance to a variety of for- and nonprofit grocery stores, as well as food retailers owned and operated by local governments. The bill would give permission for the planning office to enter into contracts or grants for managing financial support, including technical help, while also promulgating rules for the new grocery initiative.

Underscoring Sen. Brown’s statistics on food deserts, a 2019 study from the Delaware Journal of Public Health determined that there were two areas in need of support to increase access to healthy food: Wilmington and its southeastern suburbs, and central Sussex County.

In the state’s largest city, there are high concentrations of low-income residents and recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program who lack a sufficient number of grocery stores, the study reports.

In addition, it reads, in the center of the southernmost county, many rural residents who receive SNAP benefits cannot reach a store to utilize them without driving over 20 miles.

The coalition of health professionals who contributed to the 2019 report determined that an increase of retailers who accept the nutrition benefits could improve the situation in Wilmington and its suburbs.

Meanwhile, in central Sussex, the report determined that an increase to such access through mobile units or transportation assistance may be necessary.

Food accessibility has also been an area of focus for Reps. Shupe and Moore, whose proposal aims to tackle poverty from the root, by ensuring that young Delawareans are best prepared to learn every day at school.

House Substitute 2 for House Bill 125 is the combination of two initial proposals from the lawmakers.

Following its introduction in April 2023, Rep. Moore hosted a roundtable with a number of educational stakeholders, who noted that barriers like food deserts and accruing debt that prevents students from receiving a hot school lunch can impact their success.

“We see the needs every day with students that are living below the poverty line, residing in temporary living situations and coming into school hungry,” said Gloria Ho, a social worker at Milton Elementary School. “Students experience family situations that are beyond their control.”

The measure has changed a number of times since its start, as it originally carried a fiscal note that totaled an average of nearly $41 million over the next three fiscal years.

After Rep. Shupe and Rep. Moore paired their efforts — which, instead of providing free breakfast and lunch for all students, would extend the benefit to those eligible for federal reduced-price meal programs — that price was cut down to an average of $247,000 over each of the next three years.

“This was about saying, ‘Is there a way that we can help the families really in need but also bring down that fiscal note?’” Rep. Shupe said. “That’s when I came up with the idea of helping the reduced-lunch kids with getting the part that’s not covered by the federal government but also not funding families that are making larger sums of money that can afford it.”

The twice-substituted version of HB 125 has since passed the House Appropriations Committee, where the chamber’s half of the Joint Finance Committee approved the legislation, along with its fiscal note, sending it to the floor for a final House vote.

In the Senate, Sen. Brown’s bill awaits approval from its budget-approval committee. His legislation carries a cost of more than $500,000, beginning in fiscal year 2026, and if it is released from committee, it will head to the Senate floor for a final vote.

Staff writer Joseph Edelen can be reached at jedelen@iniusa.org. Follow @JoeEdelenDSN on X.

Members and subscribers make this story possible.

You can help support non-partisan, community journalism.

Other items that may interest you

By

By