1962 Delaware storm photo brings back memorable mission

By Andrew West

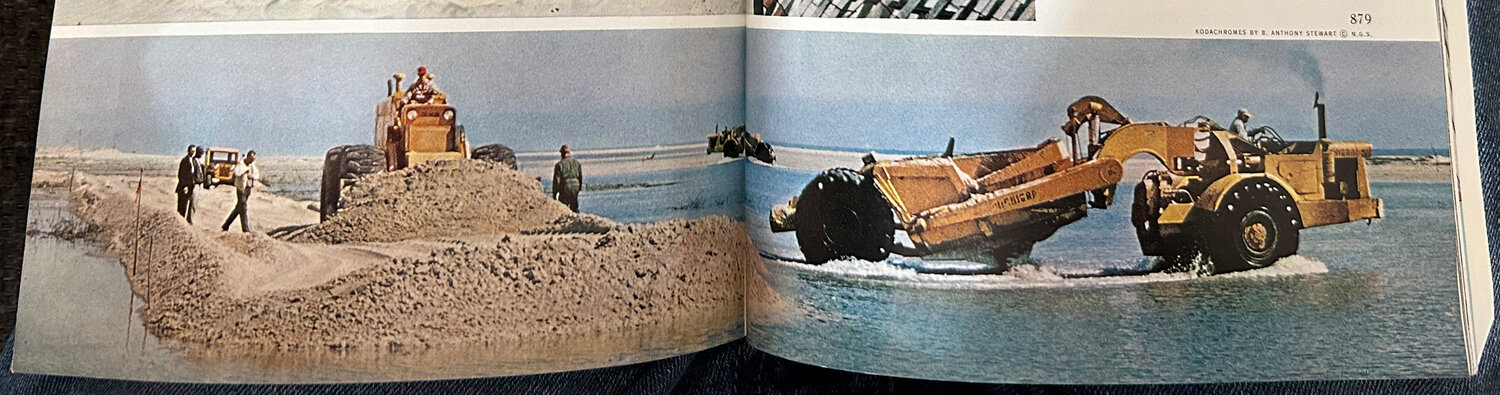

By Andrew WestFELTON — Before you read on, study the photo across the top of this page.

It was taken shortly after the Storm of ’62. A nor’easter had stalled off the coast, battering the Delaware coast with waves and wind for three straight days in early March of that year.

The young fellow with the red hat on the bulldozer is Leroy Betts.

To the left, the man in the white jacket was his boss, Melvin Joseph.

The two are best known for building then-Dover Downs International Speedway. Mr. Betts served as supervisor of the high-banked, asphalt track project for Mr. Joseph’s heavy construction company.

On the beach in the 1962 photo that appeared in National Geographic, Mr. Joseph was there with two Army Corps of Engineers representatives. Mr. Betts was pushing sand into an extraordinary hole the storm had created.

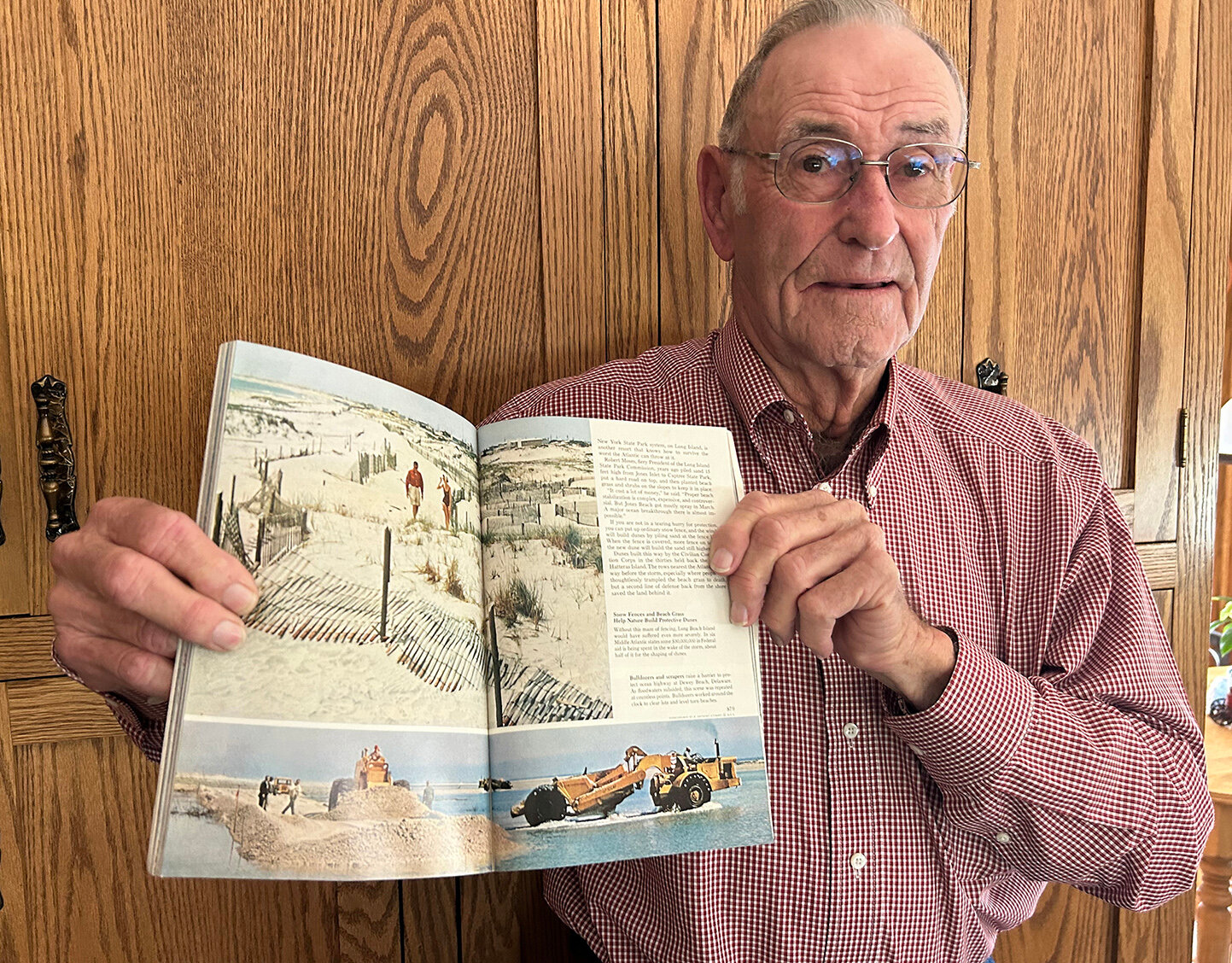

On Thursday, Mr. Betts shared the backstory of his time on the beach. Of the countless news column inches over the years, this is a story that has not been told.

As the storm and tides stacked more water in the Inland Bays, Mr. Betts was there operating a crane at the first lagoon in the community of Pot-Nets along the back bays of Sussex County. Water rose like they had not seen before, so he and another crane operator had to cease operations and back out.

Not long after in a construction trailer, someone came looking for Mr. Betts. The message was that Mr. Joseph needed him in Dewey Beach where he was waiting with members of the Corps of Engineers.

A pan – what is shown on the right side of the photo above – was taken down there. It was one of several construction vehicles that Mr. Betts, then 22, knew how to drive.

“Melvin said, ‘We’re going to get in this bowl and we want you to take us to the inlet,’” said Mr. Betts.

And, sure enough, they put a ladder up on the side and into the bowl of that pan. Mr. Joseph, the engineers and a leader of the state highway department piled in.

Mr. Betts said they let some air out of the tires to get across the sand and headed south with Mr. Joseph and the other peeping over the side of the bowl out in the cold, open air to survey the damage.

No one had already traveled ahead, so there was no clear path. Occasionally, there would be a patch of the beach highway’s pavement in view.

“I didn’t have any trouble on the sand, but we had to watch out because I’d see these holes,” Mr. Betts said. “I was driving real slow.”

Mr. Betts said he knew there were two wooden bridges on the highway on that narrow stretch of land, which is bordered by the ocean beach and the Delaware Bay.

The first bridge was swept away and resting just about in the bay. Sand had filled in the ditch, so they were able continue.

The next bridge, at what is known as Savages Ditch, was gone, too. The storm pushed it south “probably about a quarter mile” into the brush near the area of today’s Indian River Inlet Marina, Mr. Betts said.

Knowing the ditch, which was connected to the bay, didn’t extend all the way across to the ocean, he steered the pan close to the ocean and kept rolling.

Farther down, the Old Inlet Bait and Tackle Shop, where he and his father would stop on fishing trips, was gone. All that was left standing was a Gulf gas sign and a pitcher top water pump.

When they returned from the trip to the inlet, the corps contracted Mr. Joseph’s company to restore the dune line along the highway.

In 1962, Mr. Joseph was 22 years into his operation of the construction company. He once told this editor about how his business started with just a shovel and a dump truck.

As the photo suggests, the work was done in the open air. They didn’t have heated cabs on any of the heavy equipment at that time.

After the project from Dewey to the inlet, Mr. Betts said Mr. Joseph sent him into Rehoboth Beach where the devastation was surreal.

“When I first went to Rehoboth and saw boardwalk pilings and all the deck gone,” said Mr. Betts, “I just couldn’t believe it.”

The exterior of the Atlantic Sands Hotel was sheered off. He said it looked “like a little girl’s dollhouse where you look in from the back and see the beds in the rooms.”

Sand that had washed back in after the storm accumulated closer to the shoreline. Using the bulldozer and taking care not to get stuck in soft areas near the surf, Mr. Betts pushed it up to form dunes in front of the battered businesses and homes along the boardwalk. They also trucked in sand from a pit.

“I never left there until Memorial Day,” said Mr. Betts. “It was seven days a week, 12 hours a day.

“We graded that whole beach from Dewey all the way up to the Henlopen Hotel (at the north end of Rehoboth Beach).”

In hindsight, he said never understood why dredging was not considered for restoration of the beaches after the Storm of ’62.

Mr. Betts, who went on to run his own company, got his start with his uncle James Julian right out of Harrington High School. He was mentored and given opportunities that took him upstate and into Pennsylvania on big road projects.

A friend, who learned Mr. Betts was hoping to stay closer to home and perhaps work with Delaware’s highway department, referred him to Mr. Joseph.

That photo from the beach in 1962 definitely helps tell the story.

“Anybody that didn’t see it can’t begin to picture it,” said Mr. Betts. “We were working out there and there wasn’t a dune, you just looked out and there were the waves. If you happened to have an east wind and high tide, the water would come right in.”

Members and subscribers make this story possible.

You can help support non-partisan, community journalism.

Other items that may interest you