Guest Commentary: Mother Nature is going to win — she always does

My little village on Maryland’s Eastern Shore is going to drown. What is going to be done to save it? Probably nothing.

I am OK with that.

The European settlement of Tyaskin — derived from the Nanticoke Indian word for “bridge” — was established on the banks of the lower Nanticoke River in the 1800s. Natural resources were abundant, and the village grew and prospered as a waterman community.

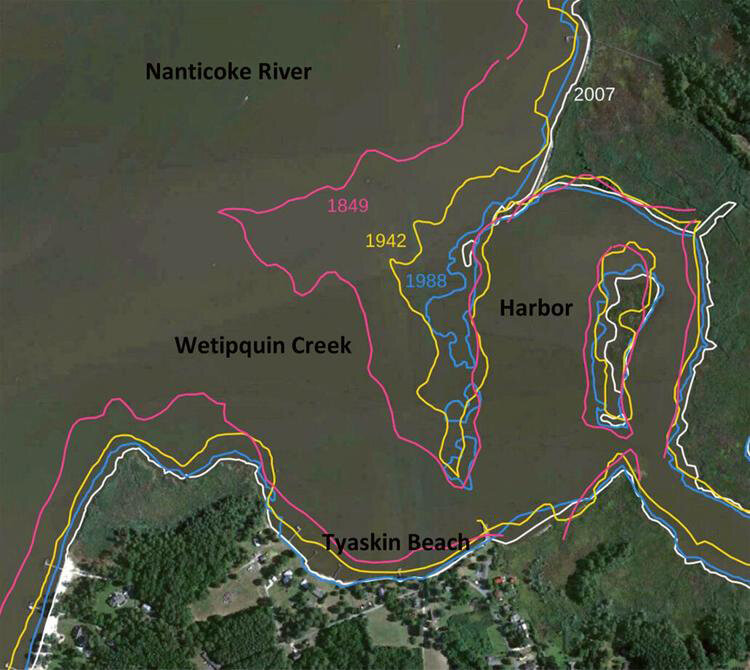

Tyaskin was blessed with a fine natural harbor in Wetipquin Creek. A nearly half-mile-long peninsula stretched south across the mouth of the creek — making it safe for steamboats and workboats to dock — sheltered from strong northwest winds and almost two miles of fetch. Over time, though, the entire peninsula washed away. From 1850 to 1950, its land mass shrank by half. It was reduced by half again between 1950 and the turn of the century.

I vividly recall teaching my young daughters in the 1990s to handle a Sunfish sailboat out there. Instead of being blocked from the river by the peninsula, they could shoot through the gaps of what had become a string of small islands.

Today, all that remains of the peninsula is a small tuft of marsh. Now, the south shore of the creek, Tyaskin Beach and the homes near the water lie naked before the elements.

Eventually, all of it — the beach, Tyaskin Park, the old steamboat wharf and probably my house — will wash into the Nanticoke River. A small, precious piece of Chesapeake Bay history will disappear, quite literally.

Should we ask for help in saving Tyaskin?

Recently, the New York Times ran a front-page story about Venice — the profoundly historic medieval city that knows the scourge of regular flooding as well as anywhere else. In 1984 the Italian government, looking for a way to stop the Adriatic Sea’s relentless incursions, approved a plan for an innovative system of sea walls at the three inlets to the Venice lagoon — an estuary about one-sixth the size of the Chesapeake Bay. They were designed to be raised when necessary to stop flooding, then lowered when the waters receded.

The original plan called for the seawall to be operational by 1995. It was not until 2020, 36 years after construction contracts were signed, that the Venice seawalls were finally deployed. The project was plagued by corruption, bureaucratic infighting and strong economic headwinds, according to the Times, and the total cost has been estimated at well over $5 billion.

By all accounts the seawall system has been a technical success, the article said. It has, in fact, prevented flooding in much of the city. But maybe it has been too successful. Predictions were that the seawalls would need to be raised five times a year. But sea level rise appears to have changed the equation: Since they were first deployed two years ago, the walls have been raised 49 times. Today there is a very real concern that the seawalls, while protecting much of Venice from devastating floods, will starve the estuarine lagoon of flowing water and turn it into a cesspool.

And there is the issue of who benefits from this work. Today, Venice has been “largely abandoned” by locals, the Times wrote, and has become a “floating and brocaded theme park” with once-banned ground-floor apartments becoming bed-and-breakfasts for tourists.

Closer to home, and on a much smaller scale, I found myself pondering those same questions at recent town hall meeting hosted by Wicomico County officials at a nearby community center: If we spend millions of dollars to keep the Bay at bay here and elsewhere, what exactly are we saving, and for whom? And just as important, will it work as planned?

At the meeting, locals expressed concerns about a breakwater the county had recently installed at Cove Beach, a few miles downriver from Tyaskin. A similar breakwater installation by the county several years ago, at what’s known as Cedar Hill Park nearby, succeeded in slowing erosion and protecting the park as a whole — but it turned the beach there into a “mudpit,” to borrow one resident’s word for it, making it unusable for recreation or for the Red Cross swimming lessons that once took place there.

Would there be, the residents asked, a similar misfire at Cove Beach? By preventing flooding in a parking lot, would the breakwater ruin the beach that the parking lot is there to serve? A Salisbury university professor in attendance made a compelling case that such a thing might indeed happen, with the breakwater depriving the beach of replenishing sand.

The county representatives at the meeting had nothing particularly encouraging to say in response. The only solution in each case, they said, would be to tear out the break water and truck in sand where needed — solutions for which the county had no budget in any case.

And that brings me to the core question. To save Tyaskin from drowning, should we expect taxpayers on the other side of the county to help foot the bill? Or if it were a state or federal project — as so many coastal resilience projects promise to be — should we ask a schoolteacher from Frederick County or a bus driver from Omaha to help pay for it?

And who is to say that a new breakwater, while effective in some fashion, won’t deprive our little Tyaskin beach of the replenishing sand that is created by winter storms.

Mother Nature is going to win. In the long run, she always does.

I for one am OK if Tyaskin eventually washes into the Bay. I only get to use what Mother Nature created for a brief time. I have no expectation that it will survive forever.

Brad Johnson is the former president of ACN Energy Ventures, where he managed equity investments in alternative and renewable electricity. Today he spends much of his time exploring the marshes of the lower Nanticoke River.

The views expressed by opinion columnists are not necessarily those of the Bay Journal. This article was originally published in the Bay Journal and was provided by the Bay Journal News Service.