Judy Johnson’s legacy looms large as Delaware great’s statistics gain new recognition

WILMINGTON — Now that Major League Baseball has officially included Negro League statistics in its record books, several Black stars are finally receiving recognition for their contributions to …

You must be a member to read this story.

Join our family of readers for as little as $5 per month and support local, unbiased journalism.

Already a member? Log in to continue. Otherwise, follow the link below to join.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

Judy Johnson’s legacy looms large as Delaware great’s statistics gain new recognition

801 Shipyard Drive

Wilmington, DE 19801

View larger map

WILMINGTON — Now that Major League Baseball has officially included Negro League statistics in its record books, several Black stars are finally receiving recognition for their contributions to America’s pastime.

Standouts like Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard and Oscar Charleston now sit atop some of MLB’s updated leaderboards, shining a light on the on-field accomplishments of countless Negro Leaguers.

Delaware’s lone National Baseball Hall of Famer, William Julius “Judy” Johnson, is one of them.

“This initiative is focused on ensuring that future generations of fans have access to the statistics and milestones of all those who made the Negro Leagues possible. Their accomplishments on the field will be a gateway to broader learning about this triumph in American history and the path that led to Jackie Robinson’s 1947 Dodger debut,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said in the May 29 announcement.

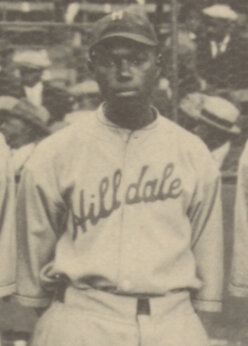

Johnson is heralded as one of the greatest Negro League third basemen of all time. His Hall of Fame plaque describes Johnson as a “slick-fielding clutch performer,” having won three championships in a row with the Darby, Pennsylvania-based Hilldale club in the 1920s and one with the Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1933.

Born in Snow Hill, Maryland in 1899, Johnson and his family moved to Wilmington when he was a child. He took interest in baseball at age 13, playing the sport in the city through his secondary years, where he attended Howard High School.

Prior to his death in 1989, Johnson discussed his experiences playing for Wilmington’s Rosedale team, which played on Saturdays against White and Black teams from around the city at 2nd and Dupont streets on the field which has since been renovated and named Judy Johnson Memorial Park.

“Baseball was my first love … One thing I worked hardest at was playing ball ... All of us, Whites and Blacks, played every chance we got at the ballpark at 2nd and Dupont… we walked to all the games,” Johnson said in a book entitled “Judy Johnson: Reminiscences by the Great Baseball Player.”

James “Sonny” Knott, 94, of Marshallton, recalled meeting Johnson at Mullins clothing store in Wilmington around 1960. Mr. Knott worked at the store and Johnson served as its night watchman. From there, the two sparked a friendship that remained through Johnson’s death.

“We became good friends, working together, going to each other’s houses. At the time, I heard he was a baseball player, but I wasn’t aware of the caliber of ballplayer he really was,” he said.

In his post-baseball life, Johnson lived in Marshallton, where his house remains standing and is a nationally registered historic place. He also served as a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies, a role he served until his retirement in 1974.

Around 1971, Johnson asked Mr. Knott to take him on a trip to Cooperstown, New York, where the National Baseball Hall of Fame is located. This became an annual occurrence, when the men and their wives would travel to view the exhibition of baseball history.

Mr. Knott recalled one trip where the men visited the home of Negro League standout Ted Page, who roomed with Johnson while teammates on the Homestead Grays. There, the former players were joined by several former Negro Leaguers, which was a moment Mr. Knott said he will never forget.

“Those guys would sit and talk about their old ball-playing days, and to them, it was just like yesterday. It was so amazing to sit there and hear that, and they would tease each other about how one got the other one out, and all that stuff. It was truly a great time,” he said.

As their relationship grew, Mr. Knott said Johnson became a father figure to him. He recalled countless occasions when Johnson would remark on old stories and legendary teammates, like pitcher Satchel Paige and catcher Josh Gibson.

After MLB’s integration of Negro League statistics, Gibson surpassed records held by baseball legends like Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, becoming the all-time leader in batting average, slugging percentage and on-base plus slugging percentage, as well as the all-time single-season record holder for each category.

“Judy talked about Josh Gibson like he was this an unimaginable man, hitting all these home runs. It’s really great to see that now he’s being recognized.”

Some of those stories included the realities of playing baseball in a segregated America, as Johnson relayed his experiences with poor accommodations, such as a lack of good transportation and available lodging options, which often resulted in Negro League players having to search for a family to room with for away games.

In addition to the park and national registry, the field at Frawley Stadium — home of the Washington Nationals’ High-A affiliate Wilmington Blue Rocks – has been named in Johnson’s honor. A statute of the legendary third baseman also stands in front of the stadium.

But despite these honors, Mr. Knott feels the state should do more to honor the life, legacy and impact of Delaware’s lone baseball Hall of Famer.

“Other than the park, you don’t see anything of Judy around the city, around the state,” he said. “I personally don’t feel as though that they give him the recognition he deserves for all his accomplishments over the years.”

While Mr. Knott was grateful that Negro Leaguers are being recognized along MLB’s record books, he wished that these stars were able to receive the proper recognition before their deaths.

“Having met so many of those guys through Judy… meeting a lot of the old ball players… it can be disheartening,” he said. “It’s a shame the old fellas are gone, because now their stats are being recognized, but they’re all gone now. They’re gone and it’s a shame they didn’t enjoy that accomplishment.”

Touting a career batting average of .304, with over 1,100 hits, Johnson was inducted to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1975 in a class that included the likes of Pittsburgh Pirates’ legend Ralph Kiner.

Mr. Knott recalled that day in Cooperstown. Despite offers to ride in a limousine to the central New York village, Johnson requested that Mr. Knott drive him, just as he always had.

“I think all of Delaware was there that day… That was one of the greatest days,” an emotional Mr. Knott said. “I always tell people, with all our praying and begging and hoping, when Judy went into the Hall of Fame that day, we all went into the Hall of Fame.”

Members and subscribers make this story possible.

You can help support non-partisan, community journalism.

Other items that may interest you

By

By